My friend Laurel teaches second grade at an all-girls elementary school. Swapping work stories one evening, she mentioned that it seemed much easier to make friends as a second-grader than as a college student.

This observation emerged, at least in part, from one little girl who had been eating lunch all alone. Laurel gave her standard advice for an eight-year-old in that situation: just go up to the other girls and ask to eat with them; ask to be their friend.

It worked. This seemed to me both predictable and totally surprising. That rarely happens with adults. We are, on the whole, not very good at vulnerability.

Why? It’s because we’re fucking awkward. We don’t want to gaff or look silly. But “awkward” is not an emotion that eight-year-olds feel, really. Shyness, hesitancy–sure. But awkwardness? That isn’t in their toolkit. We begin our lives without ego or insecurity. We know very little and are unashamed of this fact–this is how we grow. We try things, we ask clarifying questions (In the parenting world, this even has a name: the “why” phase, or the question-asking phase).

But by the time we reach middle school, the very early precipices of adulthood, it’s embarrassing –childish!– to not know something. So we focus on talking about what we do know, not asking questions to better understand what we don’t. Our shame is protective. But it’s also limiting.

I worry we haven’t escaped that middle-school territory. I worry that we’re all living in a collective, pandemic- and social media-induced adolescence, and our insecurity—while protective— is hindering our ability to connect with each other. Haven’t you noticed that modern dating is terrible? That the country is politically divided?

As U.C. Berkeley’s chancellor, Carol Christ, put it at the 2024 commencement ceremony: “We have lost the ability to talk with one another.” She meant we have lost the ability to bridge our ideological divides, but I think the sentiment applies literally, too. We need to be better at talking. We need to be better at connecting. How else will we, as Carol Christ urges, “recognize our shared humanity”?

I wonder if we should take a lesson from kids’ shamelessness. I’m not trying to say that second-graders are perfect conversational partners. They’re not. But their lack of insecurity allows them to follow their genuine interests. They ask a lot of stupid questions. They rarely hold back (for better and for worse). They’re experts at exercising the muscles of their curiosity, and they have fun with it. What if we stopped caring as much? What if we asked more stupid questions (like this one)?

I’ve been thinking a lot about the ways we connect with people. It’s been on my mind since the pandemic, really. COVID was the first time my social relationships felt charged. It was the first time I felt like I needed people, urgently needed them, and it put massive pressure on the way I held myself and engaged in conversation.

I don’t think I was alone in this feeling. The pandemic, obviously, has had a massive, lasting impact on the way we make friends and conduct friendships. Suddenly, all in-person social interactions involved a risk assessment: Will this conversation make me sick? Will it make my loved ones sick? You could be judged if you social-distanced, and you could be judged if you didn’t.

As we all remember, Zoom brought little relief.

I started college in 2020. Freshman year, most of my socializing took place with classmates in rare online breakout rooms. Online chatting felt stilted and exhausting. In some combination of vanity and insecurity, I found myself constantly glancing back and forth between my face and the other person’s face, projected next to each other on the screen. It’s deeply unnatural to watch yourself be social while you are actively being social.

With the risk of in-person socializing and the angst and awkwardness of Zoom, we all hung out less. Instead, we filled that spare time with Netflix and social media and parasocial relationships that demanded very little from us.

We no longer live under pandemic-era constraints, but we’re obviously still feeling the effects. We’re still pretty bad at socializing. (If you don’t believe me see this Atlantic article, or this Reddit thread if that’s more your thing, or this Ezra Klein episode on why we don’t hang out anymore– the “‘quiet catastrophe’ brewing in our social lives.”) Loneliness is an epidemic, and it’s growing. About half of adults reported feeling lonely in recent years. Young people are feeling even lonelier than the elderly.

So let’s chill out. Let’s be normal. Let’s start asking some stupid fucking questions.

Several weeks ago, I was on a music analysis kick. I asked friends on my private Instagram story to send me three songs: one they like for lyrics but not melody; another they like for melody but not lyrics; and a third they believe has a perfect combination of both. I didn’t get a massive flood of responses, but Jacob's was my favorite: “There, there,” by Radiohead; the aptly-titled “My Love Would Suck Without You” by Kelly Clarkson; and “I Go To Extremes” by Billy Joel, respectively.

A few days later, Ava and I played some of these songs as we made dinner and sipped red wine. We’d listen in silence for a few moments, then try to interpret the song’s narrative and themes while idly wondering what it said about the person who suggested it. We quickly found ourselves falling down a rabbit hole, cueing increasingly eccentric music culled from the angsty depths of our high-school playlists. Each song was a sort of story, a soundtrack to the characters and narrative arcs of our lives: this song I associate with Daisy, Bella, my mom… aren’t the lyrics so interesting? This song is what I thought love felt like… What do you think he meant by that…?

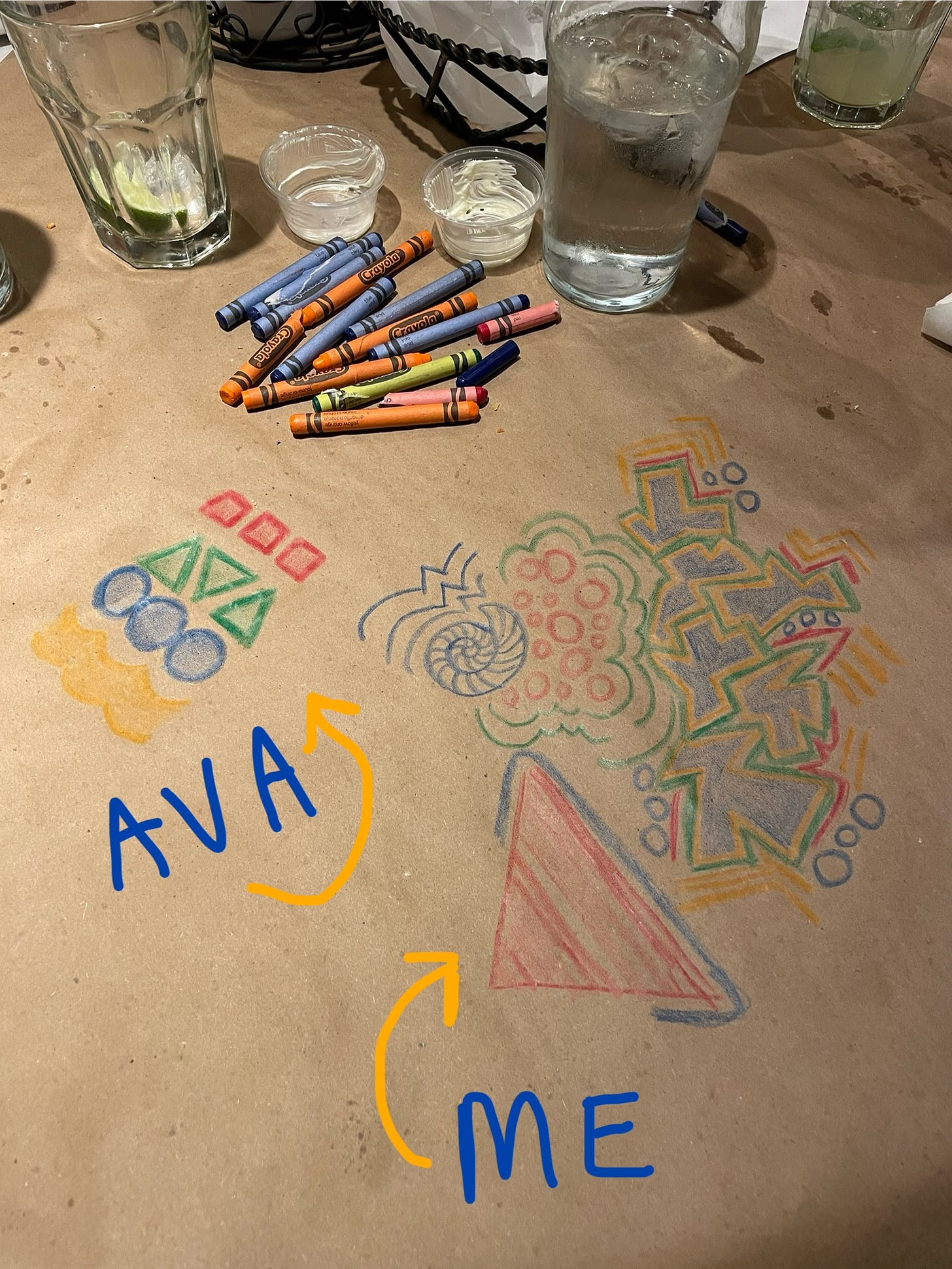

Soon any pretenses we had about our “analysis” had dissolved and we were just brainstorming silly questions: Do you have a story about a penpal? Did you have a piggy bank, and was it a literal piggy? Do you think there’s a right/wrong way to be an artist?

Fuck it, we said. Let’s ask The People. So these questions landed on my Instagram story.

This is how I learned that after a long work day, my middle school drama teacher plays Doechii and my ninth-grade summer camp pseudo-boyfriend listens to Madonna’s “Like A Prayer.”

Among my Instagram followers, 111 have been in love; 24 have not. Speaking of romance, 12% resent their first love. The other 88% are grateful for them. 106 people felt their first crush before age 13, but only 46 people had their first crush even younger, before age 7 (I fall among the 46--shout out Jaylen; in first grade I loved your smile).

Turns out that the guy I dated for part of high school was, if he’s being totally honest, a little tuned-in to the Justin Beiber/Selena Gomez drama. Also, the same guy is a little suspicious that the Kennedy assassination was an inside job (a view he shares with 67% of the other respondents; a statistic right on track with national survey data).

On average, my followers are ashamed of roughly one-third of their “liked” songs. A little less than half (47%) the respondents had strict parents. My middle school drama teacher–like 57% of respondents–did not have a rival at her elementary school (I guess some of you just didn’t need the fire of competition to get you through long division). My own elementary school rival didn’t respond to my polls. Lame!

Here’s a playlist I put together of 51 songs people said they use to decompress after work. Here’s another, of songs people think are perfect.

More than two-thirds of the respondents like their job. Understandably, the people who didn’t like their jobs were less confident that their five-year plans or career aspirations would come to fruition. On average, overall confidence hovered around 65%. Enrolled medical students (five responded to the poll) were more likely to expect their dreams to succeed (makes sense). Only one respondent claimed no confidence at all in their five-year plan. This was a very talented writer friend, and it felt a bit like an indictment of the field.

Oh–and 84% think they are less normal than the average person. Maybe that says something about what we think of as “normal.” Maybe it also says something about the people I tend to hang around.

The kinds of silly, indulgent, easy questions I’ve been asking my Instagram followers aren’t just fun, even if it started out that way, and even if they are fun. They’re also important for our shared humanity. They represent low-stakes, low-impact differences between us (you think there’s a right way to be an artist, and I don’t; you hate your job, and I don’t; you are confident your dreams will become reality, and I’m not, etc). They deepen our knowledge of each other and of ourselves, but they can also act as exposure therapy, expanding our tolerance for much larger, higher-stakes differences.

I think cultivating the habit of asking and answering stupid questions can be a practice of respecting the unique operating language of another person’s mind. The discussion that develops after the stupid question (the “why do you feel that way?” conversation) is an exercise in exploring the other person’s logic, comparing it to our own, and challenging the rigidity of our own perspectives.

Take one of my favorite recent questions: what does the inside of your head sound like?

People take this question in wildly different directions.

A few have answered using some version of the word “instructive.” In their heads lives a motherly voice, guiding and chiding them. Someone described the inside of their head as a continuous drone of white noise, through which thoughts quiver and must be identified, like faint frequencies. Someone else explained their head using the metaphor of fireworks (thoughts) exploding at random. Another described their thoughts as “loops.” Ava thinks in words over images, like flipping a picture book. I know someone who is unable to think in images. Another person says they have no internal monologue at all.

This question reveals, quite literally, how differently our brains work, how differently we think, and how those differences are interesting, not discomforting. These metaphors–loops, fireworks, picture books–can help understand a person’s thought process. It can help us build empathy and patience for their reactions, the same way we (usually) have empathy and patience for our own reactions. Once we can get used to disagreeing on small things, maybe we can begin disagreeing on the bigger things–without dismissing someone’s perspective as crazy or unreasonable.

Recently, a high school friend recited a token of social guidance her mother had given her growing up: “It’s better to be interested than interesting.” Her mom was recommending that she orient herself toward other people in conversations, not toward herself.

I was deeply struck by this advice.

Each parent gets some choice on what “parenting” means–how, where, and when to guide or critique their child. Almost always this includes some degree of instruction on how to function in the social world. Most parents, for instance, teach basic courtesy and manners: you say please, you say thanks; you chew with your mouth closed; if you have nothing nice to say, you say nothing at all (but sometimes you should tell a white lie).

What struck me about my friend’s mom’s advice was that it had to do with the choreography of conversation, not just on broad reciprocity and appropriateness in social relationships.

It occurred to me that—in a post-pandemic world, a world where our earbuds are always in and our necks are semi-permanently angled down to our phones, where we keep our precious, parasocial relationships— maybe what we need is a reminder on How to Talk to One Another. Maybe we’re living too much in our heads, worrying too much about how to be interesting in the choreography of conversation (What am I going to say? How am I going to end it? How do I ensure I won’t look silly?). So much so that we’ve forgotten how freeing it is to be interested.

There’s one thing I haven’t really addressed about my Instagram questions: that they were on Instagram.

Social media frequently gets the blame for our growing inability to communicate and empathize. I get that. Even if you were to cut out the clutter created by the platforms’ endless explore pages and algorithmic echo-chambers, it’s still very hard to be meaningfully social on social media.

I find Instagram more personal than social. For most people, it serves as a curated representation of best qualities and perfect moments. There is no space for awkwardness. It's an exhibition, not a conversation.

You can “like” something, and you can “comment” on something, but it’s not an exchange.

I loved posting these Instagram questions because I felt like I was overcoming Instagram’s greatest limitation. On a platform that makes it easy to be interesting, I was being interested. Reading the responses to my silly polls and texting the friends (and a few near-strangers!) who DMed me felt like I was actually connecting, not just showing and telling.

If you’re my age, then maybe you feel like our generation calcified the performance/exhibitionist aspects of our social media use back in middle school or early high school when we were first exposed to these platforms. But… that was also when we were still mid- or immediately post-puberty, insecure, and being puppeted by underdeveloped brains that looooooooved the quantifiable validation these sites would feed us.

But these days our personalities are almost fully baked. We should be in the process of recovering from the horrors of middle school and figuring out what we really like, who we really are. We don’t have to perform anymore. Can’t we just do what we want?

Point being: if we’re going to spend so much time on social media, then maybe we should engage more, not less. Can we be interested, not interesting on Instagram? Can we ask the stupid questions? Can we be curious? Can we interact with a post when we want to, not when we feel like we should? If we’re all addicted to these sites, can we at least use them for connection, not just exhibition?

If we don’t, I worry that, collectively, we’ll just keep exhibiting the “best” versions of ourselves to our parasocial, uninterested audiences and wonder in vain why we’re still eating lunch alone.

Give me your thoughts on this essay or anything else here.